Today’s class on Cognitive Theory, in particular, the discussion about cognitive information processing, had me thinking about the movie Memento

If you haven’t seen the movie, and think you would still like to, I will try not to spoil it too much. But I will have to discuss the salient points from just the early part of the film so if you would like to shy away, then feel free to do so.

Still here? Good. let’s talk about Leonard Shelby. Leonard, the protagonist in the film, has suffered a terrible trauma and is thus afflicted with Anterograde amnesia: “a selective memory deficit, resulting from brain injury, in which the individual is severely impaired in learning new information.” (Myers, 2006, para.1) We discussed how the brain takes very little time to decide what information to move into long term memory and what to discard. In the movie, Leonard is unable to process short term memories into long term memory. He can remember events from before the traumatic event, but cannot make new memories since. A real shame, as he has thoroughly embraced the idea of tracking down his wife’s killer.

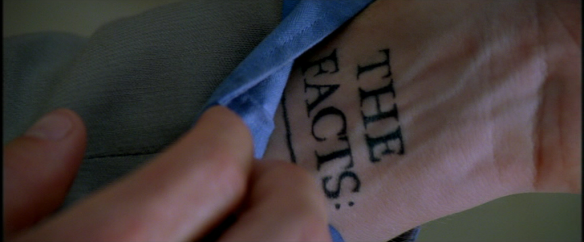

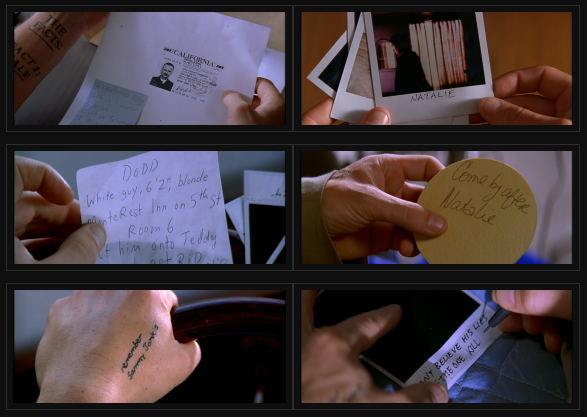

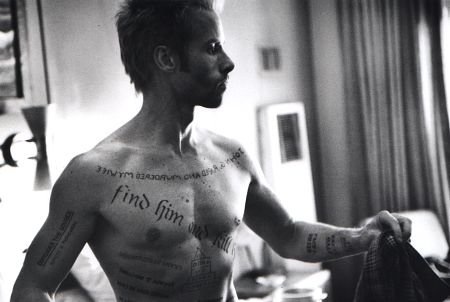

Because he can only remember facts anywhere from about 30 seconds to a couple of minutes at a stretch, he must resort to taking polaroid photographs, writing notes to himself, and tattooing the key clues to his wife’s murder on his body. He befriends a police detective who is also trying to help, albeit with tongue in cheek. Leonard is certainly not a professional investigator, and with his disability seems to be getting nowhere. But Leonard forges on, firmly of the belief that one day revenge will be his, and yes, it will be sweet.

Because he can only remember facts anywhere from about 30 seconds to a couple of minutes at a stretch, he must resort to taking polaroid photographs, writing notes to himself, and tattooing the key clues to his wife’s murder on his body. He befriends a police detective who is also trying to help, albeit with tongue in cheek. Leonard is certainly not a professional investigator, and with his disability seems to be getting nowhere. But Leonard forges on, firmly of the belief that one day revenge will be his, and yes, it will be sweet.

This brings to mind not just our discussion of cognitive theory, but of that little ‘devil in the details’, gathering data in research. Leonard Shelby’s quest is driven purely by facts. The clues he gathers must be immediately written down and catalogued, as they are his only way to coherently put together a history. His ‘research’ is tattooed all over his chest and arms. His references are jotted on cocktail napkins, bar coasters, matchbooks and polaroid photographs. But slowly he is working on solving his question. And once he has it figured out, his intention is to murder his wife’s killer.

How would Leonard’s research methodology hold up in the real world? Would this method bear fruit? Not likely. In Leonard’s case, any new knowledge he gathers disappears after a couple of minutes. His only way of maintaining custody of the information is to commit it to writing. Can this be any way to proceed with something of such grave consequence? Someone should share some research methodologies with him. Not that he would remember them, anyway.

References

Myers, Catherine A. (2006). Anterograde Amnesia. Memory Loss and the Brain. Retrieved from http://www.memorylossonline.com/glossary/anterogradeamnesia.html

Images copyright Newmarket Films

Using Memento is a great correlation. It makes me wonder about the construct of writing and the presentation of discernible facts. For me the hope is that when I finally turn out a finished project that it will be identifiable and viable in its intent or will it simply be random scribblings tattooed across the page as it were.

It is my hope that, unlike Leonard, the process of finding answers will be trans-formative or at least constructive so that the end result will be coherent. The nature not just research but identifying a question and focusing on a topic seems so far away right now.

My ultimate goal is to end up finding my path and not experience the same finish that Leonard did to his story. I might follow up this reply by watching ‘Lost in Translation’

I remember Memento, it has been awhile, but it was good. In the interest of not spoiling the movies ending I will try not to reveal much. I remember it having an interesting ending. from what i do remember (without giving the ending away) is the his police friend had a definite bias and used Leonard on several occasions. I like your correlation with research. It is at times how I have felt this week. Getting bits and pieces of information, writing them down, hoping that the information you are getting is correct and unbiased. then drawing a conclusion in hopes you remember what exactly the question was in the beginning.

Lost in Translation may be another adequate film to describe how I felt at times as well. My favorite scene is when the Producers goes on a rant in Japanese and when Bill Murray asks his translator what was said, she says “ He says you do fine” or something like that. I went to that movie with a friend of mine that understood Japanese, they were laughing through the entire movie because of the dialog that was going on in the background. When I asked what they were saying, there response was, “ah, it is too hard to explain”.

I just watched Memento…wow.

I know, right?

Is it a holiday in Vancouver tomorrow? What is it called?

It’s BC day here – but a happy Heritage day to you!

As you know, this is one of my favourite posts of the entire cohort. I love the movie, and can’t wait to watch it again this week. Your post got me thinking about self-referential theoretical research. Ultimately, we can only refer to what we know or think we know. What was there before the big bang? We don’t know, so for those of us who believe in it, the big ban theory becomes the starting point for one of many of debates on the origin of the universe based on it. I picture the tree of knowledge floating on nothingness (or non-non-matter, an impossible artificial construct). Leonard Shelby goes back to the beginning, methodically, every time, to construct and reconstruct his narrative. His findings are based on his own earlier findings, which are at some point based on an assumption, a belief, or faith. Before I get too hung up on the existential threat of meaninglessness, allow me to share a quote from one of my favourite books. As the following joke demonstrates (seriously? a joke?), we shall not “envision ourselves as having unlimited possibilities with no constraints on our freedom”:

“Two cows are standing in a field. One says to the other, ‘What do you think about this mad cow disease?’ ‘What do I care?’ says the other. ‘I’m a helicopter.'” (Plato and Platypus walk into a bar… understanding philosophy through jokes, by Thomas Cathcart and Daniel Klein)

Comments are closed.